Experience of visiting any distillery is unique and worthless, especially when you can directly talk to a people, who give all their time and passion to the creation of whisky. In November 2018 I was happy to use a chance to visit Waterford Distillery on the banks of the river Suir in Waterford, founded by the former co-owner of Bruichladdich distillery on Islay, Mark Reynier.

The distillery was converted from a modern brewery in 2015. That is why at Waterford they use “hydromill – mash converter – mash filter” system instead of conventional “Porteus mill – mash tun (lauter tun)” chain. This unusual system (though it is not unique – for example, Teaninich has something similar to it) allows receiving a very clear wort, which, as believed by many whisky geeks, makes new make spirit more fruity.

However, neither this interesting feature, together with the astonishing fact that fermentation time could last up to 170 hours, nor a surprising idea to use ex-Inverleven pot stills for distillation, draw my attention most of all during that visit and made me write this text. Terroir idea — that is the main point which I would like to share and to discuss.

The terroir idea, which obviously comes from the world of wine and means the influence of soil, climate and other specificities of vineyard’s location on the character of a final product. It definitely works with wines, but how barley and whisky could have any relation to that? Meanwhile, the whole activity and all the processes at Waterford distillery are based on this idea.

Since the beginning of 1960-es, when distillers stopped to make malting themselves and later when they started to import barley even outside the country they are in, we were told that there is no difference what variety of barley is used and from which place it is originated. A lot of new varieties of barley have been developed since that time, with more starch in it in order to increase spirit yield, but what about the taste? It is ok, no influence, we were told. Some doubts appeared when Bruichladdich, Arran and Springbank issued several whisky bottlings made of the old variety of six-row barley (Bere barley). What for, was the question, does it really matter? First seeds of doubt were planted.

Further, Mark Reynier started to exploit whisky terroir idea at Bruichladdich, and Bruichladdich continues to stick to it up to now. I visited Bruichladdich in June 2016, and for me, at that time, the terroir idea seemed more like a good marketing rather than a real thing. I perceived the idea of whisky terroir more in a way of a “distillery specificity”, which includes water, technological processes, equipment and, of course, people. For me, it was more or less obvious, as I saw that even similar distilleries on the same place (like Glen Grant and Caperdonich, for example), could give different whisky. Soil? Barley? No way.

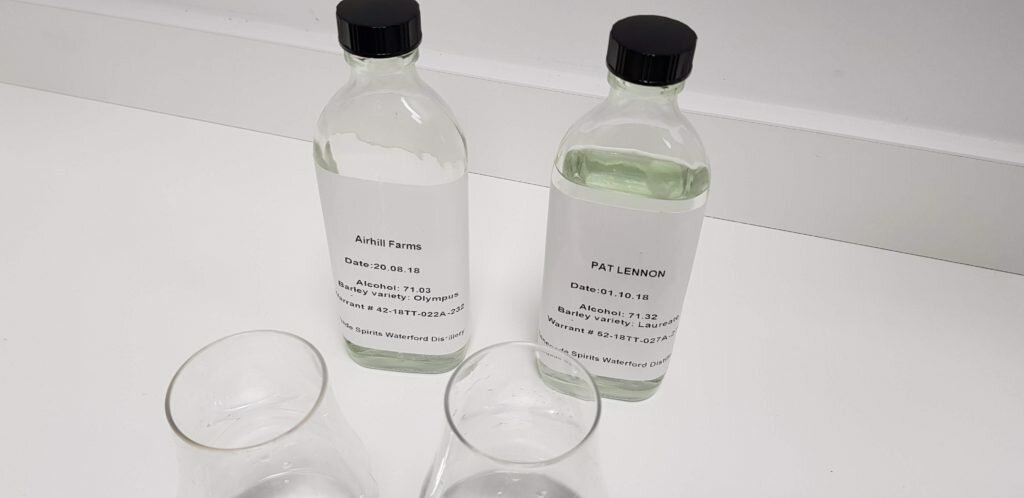

But now, at Waterford distillery, I finally had a chance to try a newmake, made from the barley of two different varieties from two different soils of two different farms. And I swear, it was two different spirits! Not absolutely different, but they were distinctively different. The least I can say – I was really surprised. It works!

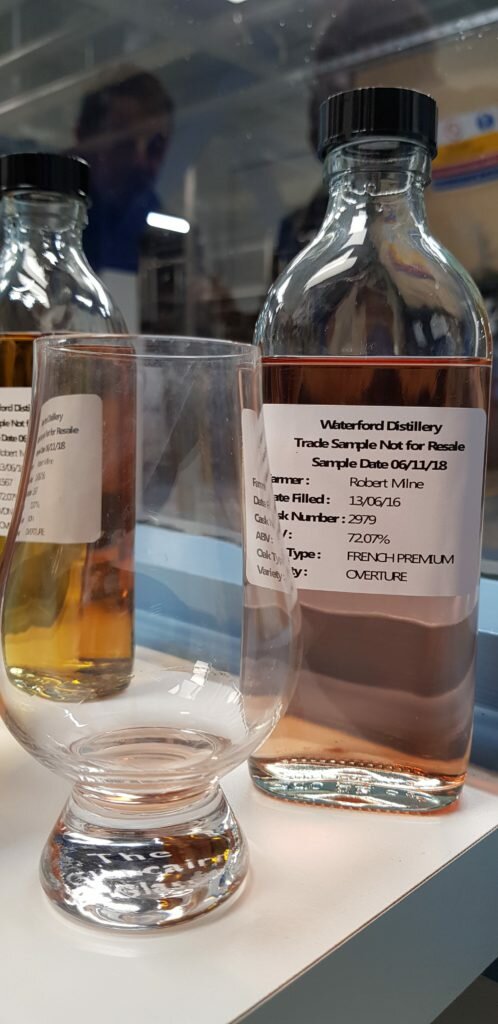

Waterford receives barley from 61 different farms with 19 types of soils. They organized outsourced malting and their production in the way that barley provenance could be traced for each spirit up to the time and place a seed was planted into the ground. They are maturing each batch from each farm separately, dividing the produced spirit in a certain proportion between ex-bourbon, virgin oak, sherry/sweet wine and wine casks – so, they will be able to make blending of whisky of the same provenance barley in order to have the more interesting and stable products. And, lucky they are, there is a hope that IWA will not act as SWA, which tries to prevent disclosure of information about the whisky in the bottle to the final customer.

And it is possible to charge for that more, isn’t it? The terroir idea seems to have also a good return potential. Could this approach blow up the market and create a specific and expensive niche? Look at the Octomore case and the ultra-peated whisky segment it has created. It still plays there almost a solo, and it pays off. But the most important thing is that terroir idea seems to have a working foundation, it’s not just a promo statement not related to the bottle content. Won’t you buy several bottles made of different barley of the same year of distillation with your friends in order to compare and to have your own opinion on that matter in something like a three years period?

As for me, I am very positive and enthusiastic about our future as whisky consumers.

Alexey Nearonov